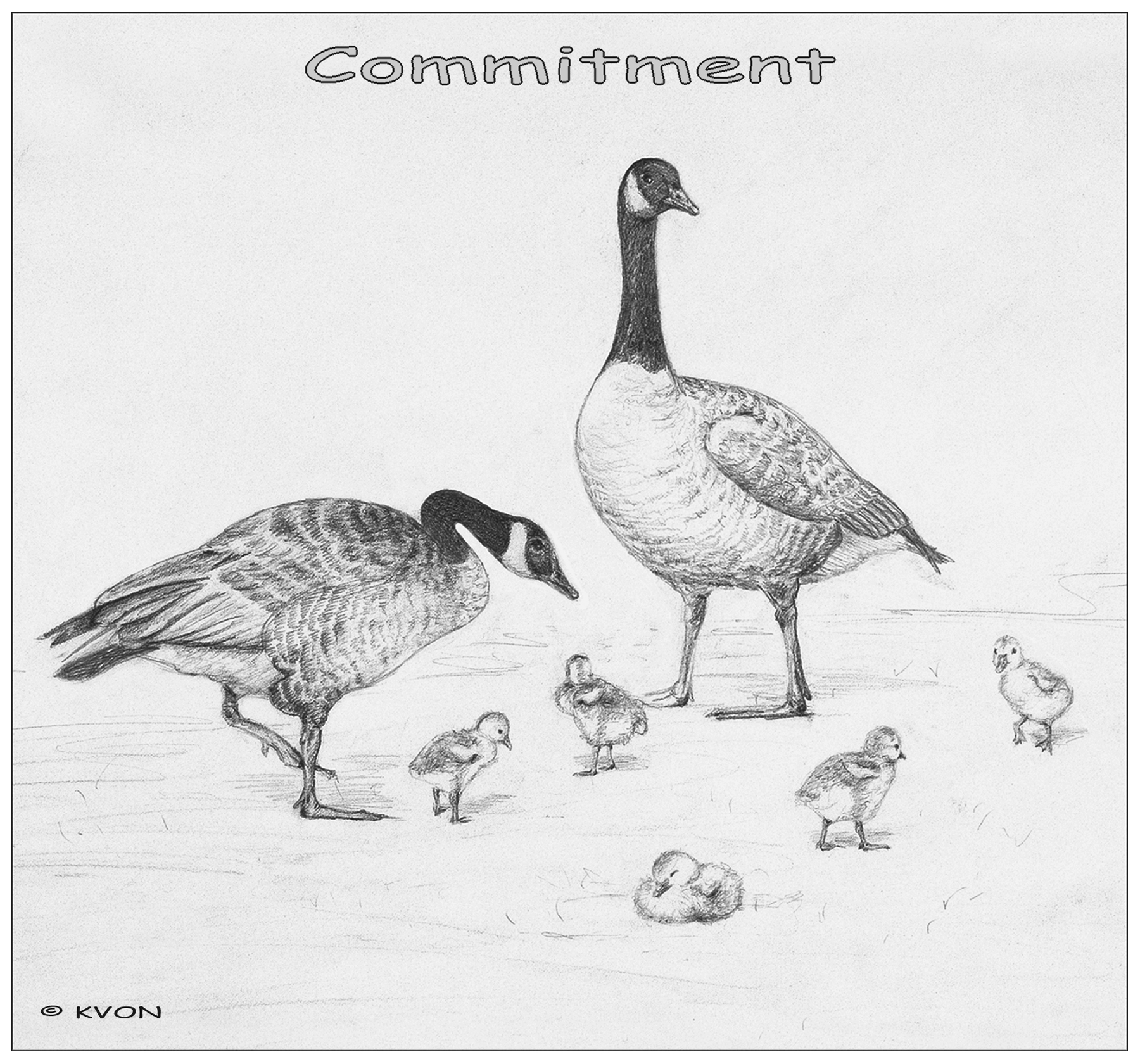

The Nature of Commitment:

(The Lesson of the Geese)

Near the small town in Idaho where I (Linda) grew up, there is a bird refuge frequented in the warmer months by Canadian Geese. I first remember being aware of the big birds each fall when I would hear their distant honking and look up to see their perfect V formations high above me, heading south. I learned from biology lectures and text books that in their yearly migration they fly high enough to find the jet streams, that they fly in a V formation to cut wind resistance, taking turns in the taxing position at the front of the V, and that they can fly thousands of miles without coming down. I also learned that by some kind of inner biological radar or global positioning, they return in the spring to the precise spot from which they left, the spot where they were born, their home.

A couple of times in the early spring, I think I saw the actual moment when some of the geese returned to our bird refuge. They swooped in looking exhausted but delighted to be home, landing smoothly on the water and noisily and joyously paddling around as though they were opening a house that had been closed for the winter.

As much as I enjoyed those early spring and late fall glimpses of migration, it was the later spring that became my favorite time for geese watching. When one of my parents drove me through the marsh lands, we would see the fluffy, brown babies paddling along in a line behind their mothers, with father always swimming close by in watchful protection. If it was windy or stormy, the mother would slow down and look back as if counting and keeping track, and the father would move into closer formation to help any that might stray. When the babies climbed out onto a steep bank, both mom and dad would help boost them up.

When I got older, further research taught me that Canadian Geese parents not only work together, they stay together, mating for life and living as long as sixty or seventy years. They stay with their children too, until they are grown, their love illustrated by their habits.

One day as we drove through the marsh we saw a mature female who at first we thought was hurt. She was making a lot of noise and swimming frantically and erratically. As we watched, we realized that she had lost one of her babies. She had the others grouped together on a bank and she would check on them and then dart off into the various passages through the marsh grass, looking for the missing one. We thought her loud, frequent honks were calls for the lost chick, but she looked up as she called and we realized she was calling for her mate. He swooped in a moment or two later and together they found the missing chick, and then hovered over it until it was re-integrated into the family. Whatever it was that he’d been doing, the dad left it immediately when his family needed him. After that minor goose-family crisis, both parents swam busily from chick to chick, nuzzling and clucking to them incessantly as if to reassure them beyond doubt that they would be cared for and never lost.

I recently read of a similar experience with a family of geese trying to cross a road. A driver came upon a father goose who had walked to the middle of the road, turned to face potential oncoming traffic, and spread his wings wide like a crossing guard. Then the mother and children began to cross. The driver, who had pulled to a stop, said she could see that the father goose was not watching her car but actually looking into her eyes to see if she was going to move toward them. When he was sure she was not, he left his sentinel position to hurry the rest of the struggling kids across the road.

Maybe it was because of the simplicity and beauty of that childhood setting and the memories I have there, but I came to love those Canadian Geese and to be awed by how far they could travel and yet always come home. To me they came to represent the commitment of families – parents who do their best to stay together, who are always there for their children, who help each other and who are predictably where they are supposed to be.

The lesson of the Geese is commitment and priority. Commitment by married spouses to each other. Deep, obvious commitment of parents to children. And the clear and consistent prioritizing of children and family above all other priorities.

The trust and confidence that we all want for our children comes naturally and directly from the open and obvious commitment of parents and from children seeing and trusting that commitment – knowing they are our first priority and that nothing matters as much to us as they do. Once children feel this, deeply and truly feel it, they will forgive us for our mistakes, for our tempers, for our inconsistencies, for all our inadequacies as parents.

But we need to learn not to assume they know of our commitment and of their priority. Children’s natural tendencies are often toward insecurity rather than security and toward doubt and guilt rather than toward confidence. We need to tell them more often of our total commitment and of how much more important they are to us than anything else.

Like the geese, we must always come home.

Like the geese, we must put our children first.

Like the geese, we must let them know by what we say and what we do that they are our highest priority and tell them often of our commitment to them.

Like the geese we must understand that commitment is the most complete expression of love.

Like the geese, we must frequently reassure our children of our love and loyalty to them.

Like the geese, if we are married, we must let our commitment to each other be obvious, letting our children see our affection and see us talking together about them and working together for them. Single parents can devote all their family commitment to their children.

Like the geese, we must relish home and enjoy being there more than any other place.