10 Best Parenting Ideas: 2. The Ancestor Story Book

Editor’s note: This is the second article in a series of 10 where the Eyres are sharing the ten best parenting ideas they have come across during their three decades of writing to and speaking with parents worldwide. The ideas are not in any particular order, but each represents a simple, practical “best practice” that can be implemented in any family. Most of them center on a “prop” or physical object that symbolizes the idea and makes it real and memorable.

As we speak to and with parents around the world, particularly in developed countries where kids are given so much, we are constantly asked what can be done to help kids develop more “grit”—to make them more motivated and determined to do their best and to fully apply themselves to the challenges and opportunities they face.

Interesting new research reveals that one of the factors that contributes most to a child’s grit and resilience is knowing the stories of his or her grandparents and great-grandparents.

One of the best things we ever did in our family was to make up a big “family tree” with pictures of our children’s parents (2), grandparents (4), great-grandparents (8), and great, great grandparents (16). Linda actually painted a big, old oak tree on a 4 x 6 framed canvas. The tree has nine branches, each with a picture of one of the children. Smaller branches go out from each of these nine, suggesting the children they will someday have. Our own two pictures (mom and dad) are on the trunk. Four roots go down from the trunk, each with a photo of a grandparent; each of these splits into two so there is a total of eight smaller roots, each with a picture of a great-grandparent. In our case we were lucky enough to find photos of the next generation—sixteen great, great-grandparents which we glued onto the next and lowest set of sixteen sub-roots.

Something about this tree painting with its quaint, old-fashioned pictures was remarkably reassuring to our children. They looked at it often, and with real interest. I’ll never forget our seven-year-old one day, idly tracing with her finger a path from her limb down through the trunk and into the roots. “I’m one-fourth like you,” she said, pointing at one of her grandmas. “And I’m one-eighth like you” as her finger went down to one of her great-grandmothers.

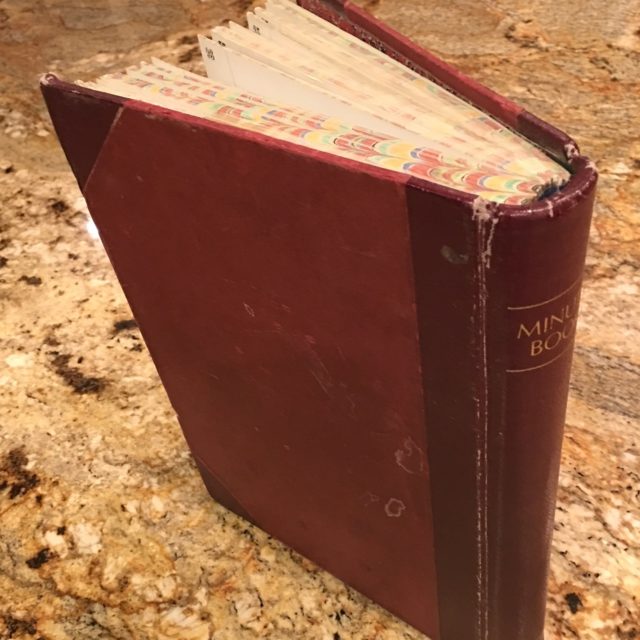

It was the popularity of the ancestor tree that led us to take the next step — the writing of our personal family “Ancestor Stories Book.” It consists of a big leather-bound book of blank pages on which we’ve written some simple bedtime stories based on actual experiences of people on the ancestor tree. There is “The Honesty of Grandpa Dean” (a story of how he hit a parked car one night on the way home from a date. The dent was small and no one saw, so he drove on home. But he thought about it, went back, found the owner and offered to pay). Or “Great Grandma Margret’s Trip to America” (how she immigrated from Sweden on a rat-infested ship).

As our children were growing up, these “ancestor stories” became their favorite bed time stories. Each connected in some way to a value — courage, responsibility, respect, sensitivity…and they were always told with the ancestor tree as a reference point. (I’m one-eighth that person…I must have some courage in me, too.”)

Not all the stories were about successes or with happy endings. Many were about hard times. The best stories, and the ones they remembered best, were the “osculating” stories—the ones that told of a difficult time that became a learning experience—stories that included both success and failure.

You don’t need a complete gallery of four generations to do this in your family. Just grandparents and great-grandparents will do. And the stories can be simple — just any experience you’ve heard — any incident that shows some positive things about an ancestor. Write them into simple children’s-story language, and perhaps have your children illustrate them.

The stories are only part of what you can do to acquaint your children with their forbearers. Create your own variations of “ancestor identity.” We know one family that makes videos of living grandparents telling about their childhoods. Another takes short vacations to the places where their ancestors came from. Another visits cemeteries and tells stories and memories at the grave sites of the people they are talking about. Still another celebrates birthdays of dead ancestors, complete with a birthday cake and candles, remembering and passing on all they know about them. The main thing is to create positive connections and to help your children feel a security and a heritage that they are proud of, that they are motivated by, that they can identify with.

See you back here next time when we will move to the third idea in our top ten.